HOW TO STRUCTURE YOUR DIET AND STRENGTH TRAINING AROUND YOUR MENSTRUAL CYCLE

You might feel as if you’re underperforming in the gym during certain times of the month. I’m here to tell you that it is not only normal, but also ideal to have this experience. It means you are a woman who is functioning within a healthy hormonal profile. To take it even further, I’m going to try and show you how to use your natural hormonal cycle to get great gains, and vary your styles of training in the gym, so that you don’t plateau, or get bored.

First, let’s break down the different stages of the typical stereotypical 28-day menstrual cycle.

WHAT ARE THE PHASES OF THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE?

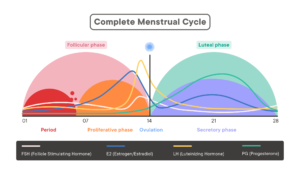

The menstrual cycle can be broken down into two phases – the follicular and luteal phases.

- The FOLLICULAR PHASE begins at menstruation, and can be separated by two stages:

- Period – lasting anywhere from 3-8 days

- Proliferation stage – lasting up to 14 days, from the day your period ends to the beginning of ovulation

- The LUTEAL PHASE begins at ovulation and ends when your period starts

WHAT HAPPENS TO A WOMAN’S HORMONES DURING THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE?

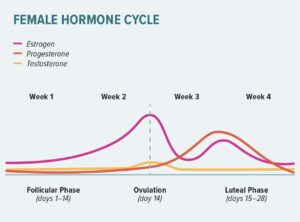

As you can see in the image below, the hormones oestrogen, progesterone, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and luteinising hormone (LH) experience transient-like effects throughout the menstrual cycle.

Even though it only increases slightly during ovulation, testosterone also plays a part (shown below).

During the follicular stage when your period begins, the pituitary gland in the brain releases follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), stimulating the ovaries to produce follicles that mature (now referred to as graafian follicles), ending in ovulation.

Oestrogen and luteinizing hormone rise to prepare for the release of the egg into the fallopian tubes as you enter the luteal phase.

LH and oestrogen levels then start to die down at the beginning of the luteal phase once the egg is released. This triggers a gradual spike in progesterone, helping the body prepare for fertilization by stimulating glandular, and blood vessel development.

WHEN IS THE BEST TIME FOR WOMEN TO BUILD STRENGTH DURING THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE?

A 2016 study by Frisen et al., split women into two groups, having one group train legs during different weeks of their cycle. The study concluded that the group who did most of their training in the follicular phase gained the most lean body mass, even though both groups did the same amount of volume.

Another study from 2014, by Song et al., had women unilaterally train their legs using a single leg press, and a single leg body weight squat over the course of three menstrual cycles. They had one leg do eight workouts during the follicular phase, and two workouts in the luteal phase. Then the second leg did two workouts in the follicular phase, and two in the eight in the luteal. The results showed that the legs that did the most volume during the follicular phase gained more strength (measured by isometric force), and also had an increase in muscle cross sectional area than that in the luteal phase, even though total volume was matched

As you can probably gather from both of those studies, the follicular phase (beginning on the day your period ends, and ending when ovulation begins) is the best time to shift your focus towards gaining strength, building muscle, and hitting your personal bests in the gym. In the week leading up to your period, the more logical training routine should have more of a HIIT, light weights, or even yoga style focus, depending on the severity of your PMS and menstrual cramps. The main goals during this time should be to maintain your routine, and to keep stress as low as possible.

Here is the practical application that I give to my clients to outline how training to the menstrual cycle can be optimised:

WEEK 1 – EARLY FOLLICULAR PHASE

Heavy Strength Focus

4-8 rep range

WEEK 2 – LATE FOLLICULAR PHASE

Volume Based for Hypertrophy (Muscle Mass)

8-12 rep range

WEEK 3 – EARLY LUTEAL PHASE

Volume Based Hypertrophy (Muscle Mass)

8-12 rep range

WEEK 4 – LATE LUTEAL PHASE

Light Weights

12+ reps

HOW TO EAT DURING YOUR MENSTRUAL CYCLE

Tweaking your diet for strength training according to your menstrual cycle is going to help you get great results.

A 2020 metanalysis pulled data from 26 randomised controlled trials and found that RMR (resting metabolic rate) was greater in the luteal phase in comparison to the follicular. Several other studies were able to determine that this increase amounted to 89-279kcal per day. This tell us that the body is expending more energy for function ability during the luteal phase. The amount of calories differ from study to study, so nothing is concrete, but the common theme they all share is a recommendation of an individualised approach to nutrition for women. The recommendation makes sense if you consider the fact that women experience menstrual cycle side effects that can be very different to one another.

THE WEEK LEADING UP TO YOUR PERIOD

One of the things we should consider for a strength building diet worked around your menstrual cycle that also promotes fat loss, is refeeding days (sometimes referred to as cheat days). I am obviously not a woman, so I’ll never truly understand what women experience, but I know from the studies, and from being told by my clients and other women in my life, that the week leading up to your period can be the worst for bloating, cramps, backaches, and other symptoms. This would be the ideal time to schedule in your refeeding days. In my experience, women tend to get the best results for fat loss having one refeeding day per week, and then two, or three in a row during the last week of the luteal phase leading up to their period, but you should structure this to suit your own situation.

To curb cravings, adding things to your diet that promote gut health could be beneficial during the week leading up to your period. Fermented foods like kim chi, sauerkraut, and kefir help bacterial diversity thrive in the gut, while psyllium help with healthy, regular bowel movements, without increasing flatulence. Complex carbohydrates such as those found in fruits & vegetables are the best sources of fibre.

Flaxseed has been known to have hormonal-like effects that has been shown to ease menopausal symptoms in some studies, which is why I highly recommend using it as a go-to source of fibre for women.

Becoming aware of your cravings duriing this time of the month is your biggest tool for success. Allowing yourself to have a bit of comfort food will reduce the chances of binging too much, and free you from the guilt that comes with it.

DURING YOUR PERIOD

It is much more common for women to become anaemic than men, and this is mainly because of the loss of blood that happens every month. Iron is needed to produce red blood cells, and to transport oxygen around the body. Low iron levels will cause low energy, so this is a great time to up your iron intake. This means including lots of red meat and seafood in your diet. Vegetables also have iron, but because the absorption gets blocked by phytic acid humans can only absorb 1% of it from plants. If you are vegan, or vegetarian you could be making things more difficult for yourself than they should be, but you can get by with iron supplements.

Vitamin C is needed for the absorption of iron, so you should be taking it during the week of your period as well. FYI red vegetables are the best source of Vitamin C.

Eliminating, or at least decreasing your caffeine intake will also help maintain healthy iron levels, as the polyphenols in caffeine block the absorption of iron. It is also a vaso-constrictor, meaning that it constricts your arteries, which can make your period cramps even worse!

CONCLUSION FOR OPTIMISING STRENGTH TRAINING & DIET AROUND YOUR MENSTRUAL CYCLE

The main point I think we can take from all of this is that staying in tune with your body as a woman is key to your fitness success. Learning how to work your training, and eating habits around your menstrual cycle can be a total game changer.

Ride the wave, sister!

Tayvis Gabbidon

Personal Trainer & Nutritionist

References:

> Effects on power, strength and lean body mass of menstrual/oral contraceptive cycle based resistance training. Frisen et al., (2016): https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26558833/

> Effects of follicular versus luteal phase-based strength training in young women. Sung et al., (2014): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4236309/

Other References:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6710244/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378432010004148?via%3Dihub

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378432010004148?via%3Dihub

https://helloclue.com/articles/cycle-a-z/the-menstrual-cycle-more-than-just-the-period

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-32647-0.pdf

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091302220300698

https://researchportal.northumbria.ac.uk/en/publications/invisible-sportswomen-the-sex-data-gap-in-sport-and-exercise-scie

https://www.nature.com/articles/0803699

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34648911/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7357764/pdf/pone.0236025.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6257992/

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00737-020-01094-0

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8296102/pdf/ijerph-18-06294.pdf

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006899310021372?via%3Dihub

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27634490/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3154522/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epub/10.1080/17461391.2021.1922508?needAccess=true

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7332750/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7916245/

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-020-01319-3

https://www.thefoodmedic.co.uk/2021/12/working-with-your-menstrual-cycle/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S144024401930814X

https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Fulltext/2021/02000/Exercise_Induced_Muscle_Damage_During_the.35.aspx?context=FeaturedArticles&collectionId=1

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25243766/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27527001/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27385613/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2425954/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8306484/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19219847/

Recent Comments